[originally posted May 8, 2013 and reposted on August 4, 2021 a week after Dr. Bandura died]

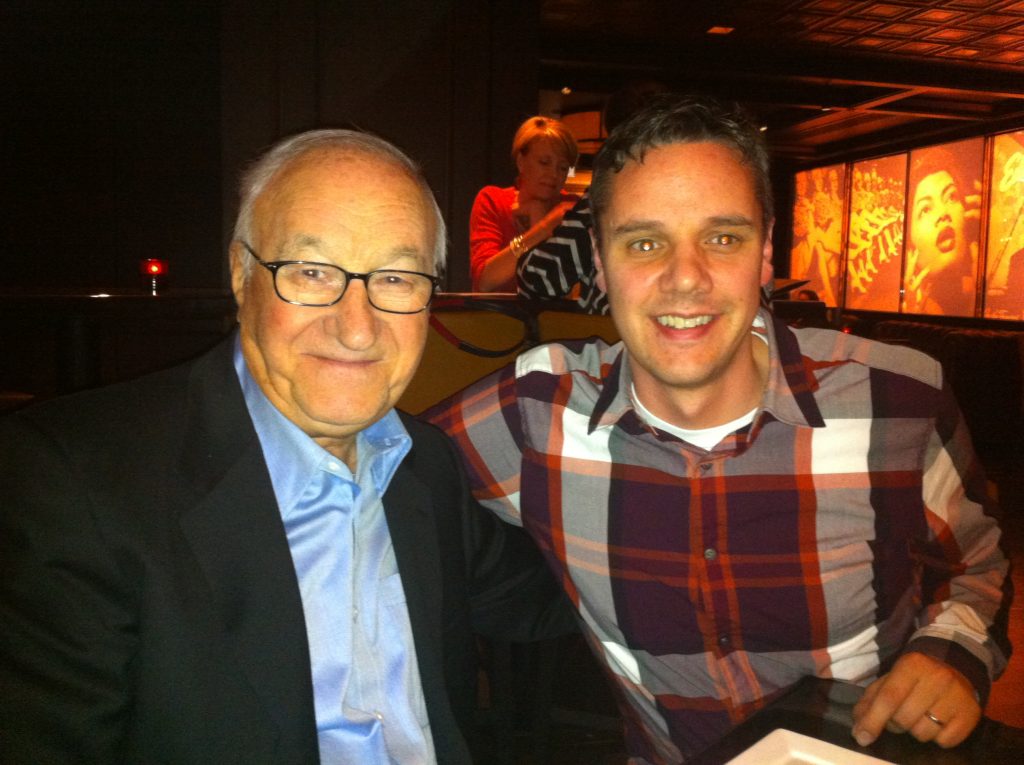

Last week, thanks to my good friend, Regan Gurung, I was lucky enough to sit down for a two-hour dinner with Dr. Albert Bandura. For those of you who don’t know of Dr. Bandura’s work, he’s arguably the most famous living psychologist (or, at least, amongst the top three) and certainly the most popular. His most famous work, The Bobo Doll Study, changed the way people thought of both learning and aggression, as it flew in the face of the accepted theories of the time, conditioning and catharsis, respectively.

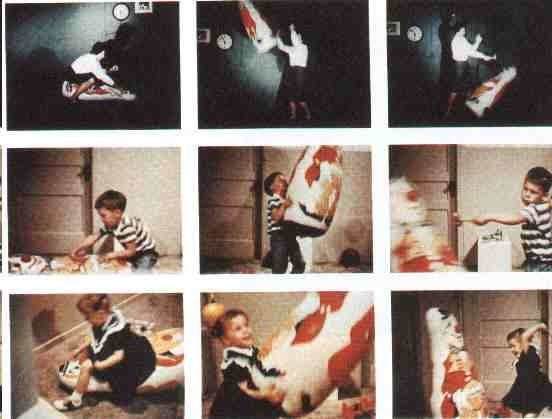

The Bobo Doll Study, first done in 1961, is thought of by most psychologists to be one of the three most famous psychology studies of all time (along with the Milgram Obedience Experiments and the Stanford Prison Experiment). In fact, if you haven’t heard of it, it’s probably because you never took an intro psych class or because you took an intro psych class a very long time ago and simply forgot (i.e., it’s unlikely it wasn’t covered). What many people don’t realize, though, is that it wasn’t just one study. It was a series of studies that led to two books on aggression and paved the way for a massive shift in the way psychologists thought about learning. Consequently, his work matters to me as a psychologist, an anger and aggression researcher, and a teacher.

I don’t mind sounding a little bit star-struck by saying that this dinner was one of the highlights of my relatively young career. It wasn’t just fun, though. It was meaningful in other ways. Here are five things I learned (or was reminded of) from Dr. Bandura.

1. Basic research matters. In my research methods course, I try and drive home to students the idea that basic research is important. Even though applied research feels more exciting and more important (wouldn’t we all rather find the cure to something than do the studies that lead up to finding a cure?), the vast majority of applied research projects find their roots in basic research. Dr. Bandura provided me with more ammo for this discussion by reminding me that his original bobo doll study was not designed with any sort of application in mind. This was a study on learning and aggression, pure and simple. Yes, it was putting behaviorism to the test and, yes, it had clear implications to a host of areas (e.g., media violence, advertising). In fact, Dr. Bandura is now working on several international projects to apply this work. But, none of that changes the fact that it was originally carried out as a test of theory with no other intentions.

2. There’s an important place for social activism in academics. Even though his work started as basic research, his current work is clearly intended to bring about social change. He described a book he’s writing on moral disengagement where he will tackle a variety of politically controversial topics (e.g., gun violence, climate change). Meanwhile, he’s involved in literacy projects on at least three continents. To those who believe that professors should avoid any sort of activism, Dr. Bandura serves as a nice example of how wrong they are. He’s doing important work that changes the lives of people across the globe.

3. The support of your institution matters. One thing I was completely unaware of was that there had been many attempts to discredit Dr. Bandura early in his career. The Bobo Doll Study, which he completed as an untenured professor at Stanford, was seen as a threat to some fairly powerful groups (television networks, advertising agencies, etc.). At one point, he was asked to testify at a congressional hearing on television violence and, as a result of his work, advertising standards were changed to cut out acts of violence. Not surprisingly, some groups worked to find fault with his research, and he even described turning on the news to find a special on him and the flaws in his research. I asked him if it bothered him and, though he didn’t answer that question directly, he did tell a story about being invited to a meeting with a Stanford administrator at the height of all this. The administrator said, “They’re saying some pretty bad things about your research [pause]. Don’t let the bastards get you down.” I can only imagine that for an untenured professor who found himself somewhat unexpectedly in the public eye, that sort of support would go a long way toward giving him the courage to carry on. I also found myself wondering if that sort of thing would happen again today.

4. So does passion. Before we even entered the restaurant, he started telling us about his upcoming book. And it didn’t stop there. He talked us through almost every chapter- not just the content, but why he was interested in it and how he arrived at his conclusions. As he talked about his work, there was an excitement in his eyes unlike anything you would expect from someone who has been doing this for 50-plus years. He is genuinely passionate about this book. He is not doing it for the money (“the sales will take care of themselves,” he said.). He’s writing it to leave at least one more mark on the world he’s already influenced so greatly.

5. Take pictures. As I said before, most psychologists will tell you that there are three studies in Psychology that stand out as the most famous: The Milgram Obedience Experiments, The Stanford Prison Experiment, and Bandura’s initial Bobo Doll Study. Regan asked him why he thinks these three studies became so well known. He pointed to three things: (1) each had social implications. (2) each involved aggression and included findings that were surprising to people, and (3) each had photo and video evidence of their findings. We spent a lot of time on this last one and how, in a visual world like the one we live in, video/photo footage goes a long way toward helping ideas stand out to people. In fact, some of the other famous studies in psychology (Mischel’s Marshmallow Test, Asch’s Conformity Experiment, and Chabris and Simons Invisible Gorilla Study) all include video footage that helps drive the point home for students and the public at large.

One comment